The Western world is in the midst of a liberal hangover. The march towards progression, equality, tolerance, and diversity appears to have hit a standstill and we are biting our nails in anticipation of what will come next. In the throes of this collective uncertainty, it is now more important than ever for those who believe in democracy to fight to uphold its values and institutions.

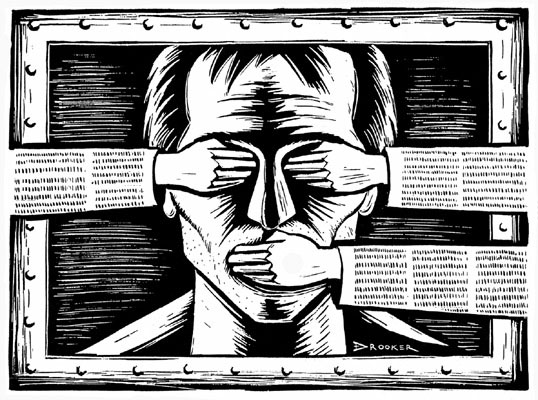

A significant element for a democracy to function properly is an informed public. The world needs societies to have access to factual information and differing opinions in order to elect their politicians and to challenge their governments whenever they feel that they are acting against their interests. This is where a diverse and vigilant media plays a vital role.

It is understandable to feel ambivalent towards the plight of the journalist when there are many other parts of society that do not function. Who cares about freedom of the press when you are suffering from daily electricity black-outs or your business is being crippled by extortionate taxes? But recent history has taught us that the suppression of the media can be a stepping stone to the suppression of the people.

Media suppression and authoritarian regimes

One of the first steps that a typical autocratic leader takes to cement their position of power is to intimidate and control the media. Milošević, Assad, Putin, and Erdoğan are all authoritarian leaders with different aims but with frightfully similar tactics when it comes to suppressing and controlling the media. Today in Turkey there are 81 journalists imprisoned out of the total of 259 journalists currently imprisoned worldwide. Erdoğan’s distaste for those in opposition is plain for the world to see. He has ordered his police to storm news organisations and continuously tarnishes the names of those journalists who dare to defy him. Putin’s Russia has never been a bastion of media plurality and freedom of expression but the control and intimidation from the state is more aggressive now than it has been for years. Under authoritarian regimes journalists regularly face incarceration and vilification for reporting stories that are critical of their governments.

Methods of control

A common ploy to disrupt the flow of information is to discredit it at all costs. This involves implying that the content being written is being sponsored by “foreign agents” or the “political opposition.” The aim is to paint the journalist as partisan and therefore unreliable. This clever tactic can smear an entire media publication in a thirty-second soundbite. The public will have little interest in investigating the sources of stories or the credibility of the journalist in order to determine their own conclusion. Facts matter not to the strongman.

The next way to guarantee that unflattering reports about the ruler and his buddies are relegated to the gutter is to pass new legislation to regulate the media. This is often done covertly, with little controversy, speed-tracked to the top of the agenda and enacted before you can shout “censorship.”

In Syria in 2011, during the first year of the uprising, President Assad shamelessly misled citizens by introducing a new law that, at face value, appeared to be an important step towards media freedom. The law was enacted to placate those protesting the arrests and expulsion of local and foreign journalists reporting on the uprising. The new legislation was purposefully vague and contradictory. It promised journalists the right to access information on public affairs and banned “the arrest, questioning, or searching of journalists.” However it also prohibited media outlets from publishing content that affects “national unity and national security” and forbade journalists to report on army activities.

Although the legislation claimed to protect journalists when a publication or broadcasting company reported anything unfavorable or damning of Assad or his regime, the authorities had the legitimacy to directly silence the journalists for endangering “national unity.” This tactic created a climate of fear for journalists critical of the government. Many journalists stopped reporting for fear of retribution and most fled the country. Assad managed to create a giant propaganda machine by controlling both the state broadcaster and private media outlets that toed the party line.

Albania’s proposed new legislation

This is why media legislation, however innocuous it may appear, needs to be examined and discussed at length before it is passed. In Albania the proposed new law directed at registering online portals with the Media Monitoring Board before the election may seem relatively harmless.

Balla, Rama, and co. will likely insist that this law will enhance objectivity and fairness during the chaotic and tense period of the election campaign. News publications need to be responsible for the content that they publish and journalists should be accountable for the facts that they purport. All these are reasonable points to make during an era of fake news and interfering propaganda. However, we need to carefully consider the possible motivations behind introducing any legislation that could be used to shut down news websites.

The 2015 Freedom House report on media freedom in Albania deemed the media in the country “Partly Free.” The report criticized the lack of transparency in relation to media ownership and the influence of powerful business people and politicians on the mainstream media. In a rare, slightly, positive note the report also concludes that “blogs and other online media offer a more independent alternative to mainstream outlets.” When online media in Albania has been praised by an independent international media monitoring body, why have the government proposed to restrict their freedom by conjuring up this law that could potentially give them the legal power to shut them down?

According to a draft of the proposed law sent to BIRN, unregistered sites that contain “electoral propaganda” will be closed down. It goes on to say “the usage of web portals which are not controlled by the Media Monitoring Board for electoral propaganda is prohibited. State authorities shall undertake measures during an electoral campaign to shut down unregistered web portals that distribute electoral propaganda, conduct polls disregarding the rules of this [electoral] code, or go beyond the limit of information and are deemed electoral propaganda,”

The vagueness of the draft proposal is worrisome. Besides the uncertainty of what a “web portal” actually is, it is unclear what the proposal means by “electoral propaganda.” Does this mean that factual news stories that are critical of the ruling party will be in breach of the rule? Will opinion pieces and blog posts that take a less than favorable view of a politician be deemed propaganda?

The internet has allowed independent and alternative news platforms the opportunity to access large audiences without having to obtain massive financing. It is important to protect diverse voices when so many mainstream media outlets are pressured into making editorial decisions based on their owners’ financial or political interests.

It is likely that those in favor of this legislation will argue that in light of the prevalence of “fake news” websites that seemingly influenced the behavior of voters in the recent US election, the government has a duty to crack down on misleading and false stories before they cause problems in Albania. But there is a huge difference between fake news sites that profit from creating outrageous and blatantly untrue stories and online news publications that publish reports with factual content, named sources, and visible by-lines. The proposed legislation could be used to tar “fake news” sites and credible online publications that offer alternative points of view with the same brush. As highlighted by Jonathan Albright in The Guardian this kind of filtering is “likely to normalise the weeding out of viewpoints that are in conflict with established interests.”

This could severely damage the credibility of publications that do actual journalism work.

The possibility that the government could use this confusing legislation to block media outlets that are less than kind to their political party is frightening. For democracy to function it needs a robust and critical media in order to ensure that information in the public’s interest is known, discussed and debated. The distance from a democracy to an autocracy is closer than we like to think, any step that hinders media freedom is a step in the wrong direction.