You can listen to a reading of this article here.

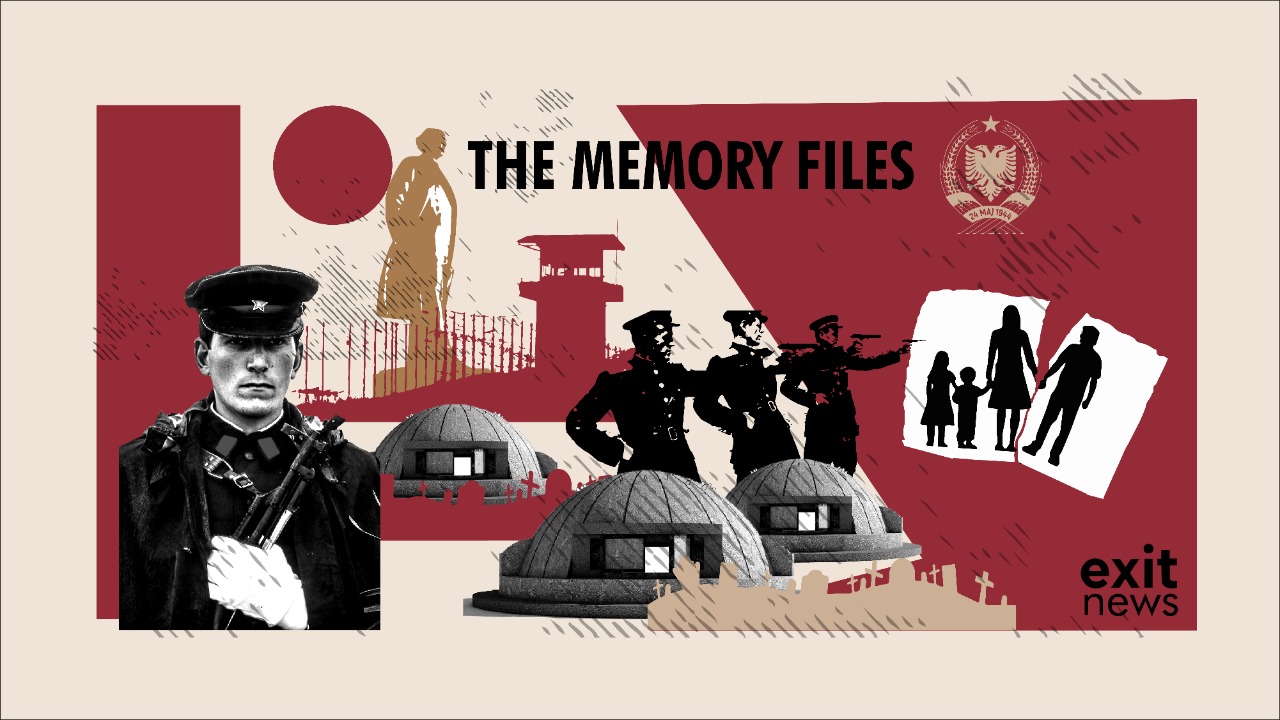

For almost 50 years, Albania was in the grips of a brutal communist regime, led by dictator Enver Hoxha. During that time, tens of thousands of Albanian men, women, and children were persecuted, imprisoned, and murdered. Many more died because of horrific conditions in prison and labor camps throughout the country.

Today, 30 years later, there are still over 6000 people still missing. There are no memorials, no justice, and many families do not know where their loved ones remains are.

The Memory Files will take a snapshot of 12 of these stories. Over the next year, we will go beyond the statistics and take a look at who these people were, what their lives were like, what went so wrong, and how their families have tried to cope with the tragedy of their loss.

Our first story begins on a hot summer day in an old neighborhood of Tirana.

The house, with its splendid balustrades and beautiful garden complete with a wall of jasmine flowers and a tortoise, was built in 1931. Next door is the home of Nazmi Ali Uruci, the man who will be the subject of today’s interview.

I bowed my head and descended three stone steps into the cool first floor of the house. The exterior of the house is finished in the Italian style typical of the period, and the interior has stone floors and low ceilings, divided with old, wooden beams. To the left sits an ancient, black enamel sewing machine, and to my right, with his back to the door, sits Hysen Daci.

The air is cooler here than outside where passersby suffer under the brutality of the city’s mid-summer sun. Natural light floods in through a large window and illuminates the features of Hysen’s weathered face. At 81 years old, his sight is failing, but he greets us with a warm smile and an outstretched hand.

Hysen is a retired engineer. Born on 11 July 1940, his family originate from Dibra e Madhe in the north of the country. His wife, Mimoza, is from Shkodra, and they have been blessed with two children. These days, they live a quiet life in the northern part of Tirana, but their presumed idyll is overshadowed by a terrible tragedy and a great injustice.

As we start the interview, the words flow out of Hysen’s mouth with gusto. It seems as if no one has asked him about his family’s tragic history for many years. He starts by introducing himself and his family, speaking with pride as he recalls their names, origins, and dates of birth.

But when he comes to mention the name of Nazmi, his demeanor shifts.

“One of my uncles was Nazmi Ali Uruci. He was born in 1904 to a Dibran family, and they lived in Manastir in Macedonia for a long time. But after World War 1, Nazmi went to the French lyceum of Korca, where he shared a room with Akil Sakiqi from Dibra and Fahri Dabulla from Gjirokaster.”

He goes on to explain that these men all attended the same school at the same time as the future dictator Enver Hoxha. Hysen explains that it’s likely they were in the same class, as Hoxha mentioned the three boys in his memoirs, referring to them by name and saying that things “ended badly” for them.

After Nazmi finished his studies, he traveled to France where he studied Dentistry. Unfortunately, his studies were cut short due to a lack of funds and he returned to Albania after two years.

He then won a scholarship to study in Italy and was reunited with Akil and Fahri, by chance, at the Military Academy of Rome. After graduating, they earned the rank of Lieutenant in the Guardia di Finanza and served in Albania for many years.

Nazmi worked as a border commander at various customs points, including Shkodra, Shengjin, Durres, and Pogradec.

But sadly, Hysen explains, it was their glittering careers that would ultimately be their downfall.

Hysen describes him as someone who loved books passionately, particularly Dostoyevsky, and his masterpiece “The Brothers Karamazov,” as well as Leopardi, Parini, Carducci, and others. He explains that Nazmi was a quiet man, often engrossed in thought, and was someone who was puritan in his approach to honesty.

The “intellectual,” as Hysen calls him, got engaged in 1934 to a young woman, also from Dibra, called Ifete Strazimiri. They were married a year later, and in 1936, their first child Aferdita was born. She was followed after two years by a son, Ali, and then in 1943 by a second son, Mentor.

They had a happy marriage. Ifete had dark hair, dark eyes, and porcelain skin. Namzi had blue eyes with thick lashes and brows and a head of bushy hair. A photograph of their wedding day taken by Albanian master Marubi shows their youth and fine attire; Ifete in a delicate dress from Italy, Nazmi in his Lieutenants uniform complete with a sheathed sword.

Hysen explains that they lived well, as Nazmi’s position was a respected one.

“They lived in good conditions because as a border commander and later a captain; he was paid well with Napoleon gold coins.”

This happy and somewhat carefree existence continued until October 1944.

Previously occupied and a “puppet state” of Italy, by 1944, communist partisans had gained control of most of Southern Albania. On 29 May, the communists called on the National Liberation Front to attend the Congress of Permet, which chose an Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation, headed by Enver Hoxha, to administer and legislate Albania.

By mid-summer, the communists had defeated the National Liberation Front and entered central and northern Albania by the end of July.

A provisional government was formed in Berat by the communists, and Enver Hoxha was appointed as Prime Minister on 18 October 1944.

After the formation of this government, Hoxha sent orders to Tirana to “settle” the matter of officers of the previous regime. This, Hysen explains, meant that Nazmi and his two friends, along with many others, were to be executed.

Meanwhile, Nazmi, Akil, and Fahri were preparing to join the communist partisans at Dajti, as they were aware they would soon enter Tirana and it would be liberated. They had negotiated through a man called Sami Koka to receive immunity and security for their lives.

On 28 October, two couriers came from the communist command on Dajti, led by Dali Ndreu and Mehmet Shehu.

Ndreu was a leading communist who in the years since the regime fell, has been noted as someone having direct responsibility for communist crimes by inspiring, organizing, executed, or assisting partisan forces in criminal acts.

Shehu, known for his brutality, was a driving force behind the regime. He was rapidly promoted through the ranks and “shared power” with Hoxha after WWII. He “committed suicide” in 1981 although there are persistent rumors that he was executed on the orders of Hoxha.

The three friends were escorted by the couriers, headed for the command at Dajti, and were never seen again.

That was the last their families heard of them. They searched in vain through November, December, and beyond, trying to find out what happened to the three men. Even when the regime of Hoxha was established in Tirana and the family made requests to the administrative bodies and directly to Mehmet Shehu, they received no answer.

“No straight answer was ever received, they evaded questions, and it was implied that the three men were executed. They are still missing after 77 years,” Hysen explains with sadness.

Nazmi was just 40 when he died. He left behind his loving wife and three children aged 8, 6, and 1. Then, just a few months after Nazmi’s death, his son Ali suffered from acute appendicitis, didn’t receive proper medical care, and passed away. Aferdita, the girl, was forced to drop out of school and find work to support the family at the age of 14.

Ifete started working in a tough, manual labor job to provide sustenance for her children. Mentor managed to complete his studies as a mechanical engineer but was refused prestigious positions due to his ‘bad biography.’

One of the most damning facts to emerge from the interview is that Nazmi was executed despite being a close relative of Hoxha’s wife, Nexhmije Hoxha. Nexhmije’s father and Nazmiu’s mother were brother and sister, an extremely close family tie between Albanians during this time.

Hysen explained that Nexhmije was well aware of this link and yet did nothing. Furthermore, when the news of Nazmi’s disappearance broke, she never visited the family, something very shameful in Albanian tradition. Not only was Nexhmije a close relation to Nazmi, but Hysen’s mother, Fatime, had taken care of Nexhmije when she was a baby in Bitola.

“When my mother died, the truth is she came to pay her respects at my house, but for all other cases, including Nazmiu, she didn’t come. When my father and uncles died, she didn’t set foot in our house. There was complete silence from her.”

In terms of how they were treated, Hysen said they didn’t face much persecution. But when he spoke about their life during those years, you cannot help but wonder if his perception of their reality had been warped and almost normalized.

“In our house, as the family of Nazmi, the communist state sent 14 others to live here. They sent an Egyptian family with seven members and another family from Korce. Nazmi’s widow was left with one room and a shared bathroom for 20 people. It was tragic from this point of view,” he said.

Hysen added that the family suffered extreme poverty from the moment Nazmi was executed and struggled to survive.

But their time during communism could have been much worse if it wasn’t for the protection of a communist called Xhaffer Qineti, who lived nearby. Hysen explained that he protected around five or six politically persecuted families in the area, mainly from Dibra.

“He was a sincere man; he had the prestige of being a communist and protected us a lot, as much as he could then. He protected our families a lot from deportation. Out of six families, three had members who had been executed,” he added.

But what about the family’s search for justice and answers as to Nazmi’s fate?

“After the fall of the communist regime, Nazmi, Fahri, and Akil, all three who had the same tragic and painful end were declared martyrs of democracy. Their names are on a memorial at the headquarters of the politically persecuted. They were decorated by the President with the title Honor of the Nation. But the paradox is, they are accepted as victims of communist terror…but still today, their sublime sacrifice is not known.”

Hysen explained that there is still no official line on what happened to them, or where their bodies are, despite the awarded titles. He added that he is aware of at least 40 others who were executed around the same time, between October and November 1944.

“Many of them were executed, disappeared, and missing, and it’s tragic and unfair that families are not recognized for the right compensation. Those executed without a trial at this time, their end is more tragic than those executed but where a trial took place. They had the opportunity to speak out to defend themselves, even if they weren’t successful,” he explains.

For people executed after trials, even if they were shams, the families generally know where the bodies and remains are buried. This was not the case for Nazmi’s family, and it has cast a long shadow over their lives.

“Whenever October and November came, my mother used to cry for one month for Nazmi. She would shed tears for his tragic end,” Hysen said, adding that his mother died in 1988, meaning she mourned him for over 44 years.

“She had a great deal of compassion because he was a very gentle, family man. The research that we did over the years didn’t yield anything,” he said, shaking his head.

Hysen talks of rumors and newspaper articles that mention Nazmi’s fate over the years, yet there is nothing concrete. People speculated that they were shot in the north-eastern area of Tirana, near the Lana River, but the family has never even been able to confirm the exact date of their execution.

Documents only state the day they were presented to the communists—28 October 1944.

“They didn’t even have the courage to admit they executed them,” he adds with disgust.

He spoke at length of the “witch hunts” conducted by the communists, right until the end. He also spoke several times about the fact that killings by communists started before the formal date recognized in the history books.

Interestingly, the Albanian government recently passed a law forbidding the Institute for the Study of Crimes and Consequences of Communism (ISKK) to study any events or crimes committed before November 1944.

The ISKK had previously worked on studies of communist crimes and activities, covering 1941 to 1944. They argue that this period is crucial as it paved the way for the regime. One study included 265 names of communists involved in shootings, burning houses, robbery, and murder. The government, led by the Socialist Party, who are the direct descendants of the Communist Party, opposed the report’s publication and later imposed the ban.

“Yes, the killings started before the formal date that is known. What is this formality? At least 30 or 40 were killed during October-November 1944, before 29 November. And yet why is this 29 November considered the beginning of the communist regime? It began on 24 May in Permet, and even before” he said with slight anger in his voice.

As we came to the end of the interview, I asked him how he feels about Nazmi and what he remembers of him today.

“I was just four years old when he died, but I remember him, talking to him…I have a great affection for him. I remember I had a dream that I still remember to this day. I dreamt he came to me, but I realized that it wasn’t real when I woke up. I was always curious about what happened to him.”

In terms of the rest of the family, he said they are running out of time and hope that they may ever be able to find out the truth. Nazmi’s only surviving child, Aferdita, who is now 85, is still holding on to the dream that they will find, if not justice, at least closure.

Mentor, the youngest son, died eight years ago. Hysen explains that he died with great pain in his heart over the lack of justice and dignity for his father. He explains that Mentor would say, “What is dignity when my father is ignored? We need to regain our dignity.”

Our interview comes to a close, and Hysen sighs;

“All losses of life are painful but without name or grave, without justice, without motive…leaving the family in misery with three children, the youngest just one year old… at such a young age, just 40! Sublime sacrifice is the ultimate sacrifice.”

With thanks to the Daci and Uruci family, in loving memory of Nazmi Uruci, 1904-1944.

This article was created with financial support from Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung.