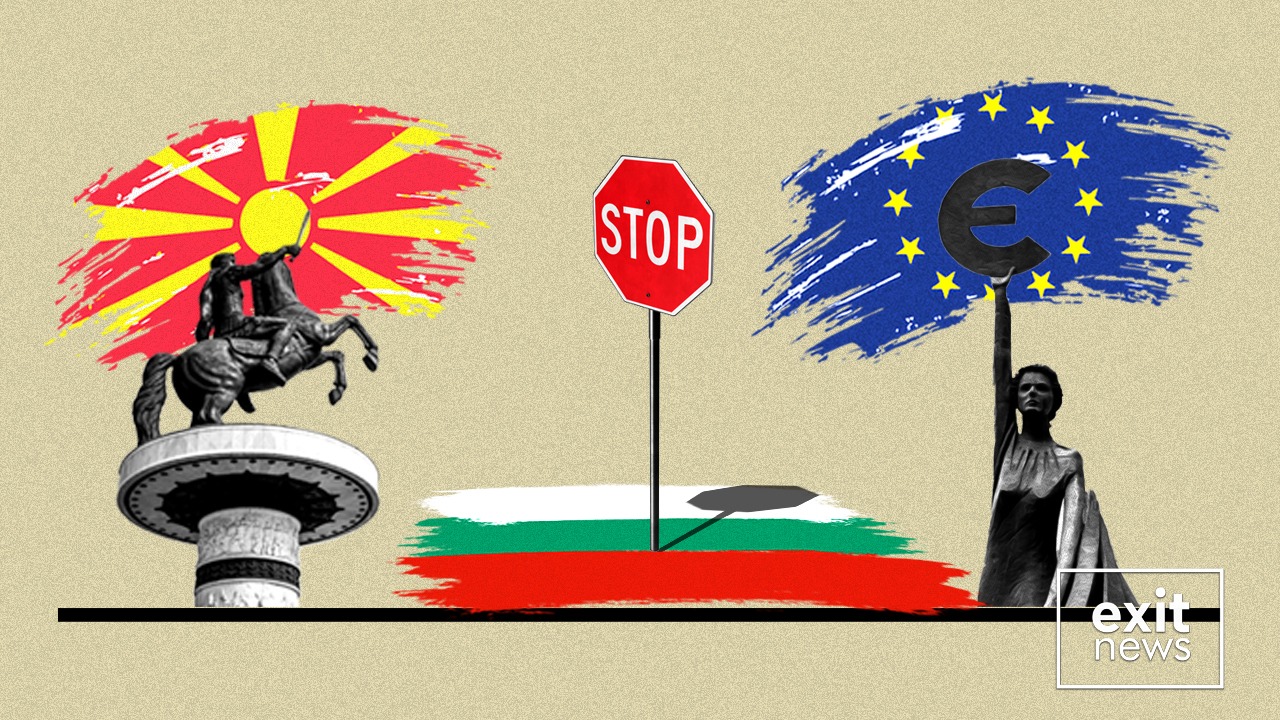

A member of Bulgaria’s ruling coalition has hinted that the results of North Macedonia’s census, in which only some 3500 Bulgarians were officially recorded, could hinder its European Union accession aspirations.

North Macedonia is currently in the EU waiting room following a veto from Sofia over a dispute on language, culture, history, and alleged failure to preserve the rights of ethnic Bulgarians in the country. Skopje denies the claims.

The results of the census, carried out in 2021, were published on Wednesday (30 March). In the results, it was reported that just 3,504 people identified as Bulgarian. This is a far cry from the 100,000 claimed by Bulgaria.

Slavi Trifonov, leader of ‘There is such a people’ party, a ruling coalition member, said that more than 100,000 Macedonians have a Bulgarian passport. He said that acquiring one meant they had proven their Bulgarian roots, but were afraid to declare themselves as such in North Macedonia.

“Ïf North Macedonia is the European country it claims to be, would anyone be afraid to say who he really is?” Trifonov commented.

Other observers say people only take a Bulgarian passport for practical EU-related reasons and to facilitate visa-free travel and emigration.

He continued that as long as the citizens of North Macedonia cannot freely express themselves and their rights are violated, “the country will remain part of the Western Balkans only”.

This comes despite whispers in both Sofia and Skopje that the veto could be set to be lifted, due in part to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In a bid to increase regional stability, some diplomats have spoken off the record that an agreement has been struck that could pave the way for the official start of negotiations to launch in June.

Interview: Bulgaria Should Unblock Veto and Solve Issues in Chapters Stage

Macedonian’s however, claim there is no discrimination against Bulgarians in the country. In an interview with Exit, Metodija Koloski, president of the United Macedonian Diaspora said the country has already made a significant number of changes to meet the requirements of Bulgaria, Greece and others. In 2019, Skopje agreed to rename the country as North Macedonia, following an agreement with Greece.

“If we continue making these concessions, what will be next? If we agree to these, how do we know what comes next and what they will ask us to do? We have made many changes, it is time to get things moving now and work out the rest later,” Koloski said.

Koloski said Macedonians do not hate Bulgarians but are growing tired of Sofia’s policy of negating their identity, culture, and globally recognised (including in the EU) language.

He voiced his belief that there is more to Bulgaria’s veto than just squabbles over terminology, history, and the constitution.

“Bulgaria was the first country to recognise Macedonian independence, Bulgaria welcomed thousands of Macedonian refugees from different wars, and now, you have Bulgaria, the number one stumbling block.”

“This should be a non-issue, but someone is making it an issue. Then we come to what is really behind this. I don’t want to throw this in, but you know, the Russians have an interest in making sure that enlargement doesn’t proceed.”

The population of North Macedonia is 2,097,319, including residents and the diaspora, of which 54,21% identify themselves as Macedonian, 29.52% as Albanian, 3.98% as Turk, 2.34% as Roma.

However, the Macedonian SSO excluded the information on the overall population from their summary of census results, and instead presented only the number of residents in the country.

When residents only are considered, 58.44% self-identify as Macedonian, 24.30% as Albanian, 3.86% as Turk, and 2.53% as Roma.

According to the data, just 0.16% identify as Bulgarian.