Last week, I have been trying to make sense of the actual process of installing the new judicial bodies of the High Prosecutorial Council (KLP), High Judicial Council (KLGj), and Justice Appointments Council (KED), and how the current state of the vetting most likely in all three cases will necessitate additional rounds of applications before all positions can be filled.

This would automatically lead to a further delay in the installation of these bodies, which in turn would further delay the installation of the Constitutional Court, the Special Prosecution (SPAK), and the National Investigation Bureau (BKH). This would result in the (possibly indefinite) extension of the lawless situation in which Albania currently finds itself, with the highest judicial bodies permanently incapacitated.

Since the bipartisan adoption of the main justice reform legal package two years ago, it was clear to all actors involved that politics moved at considerably slower pace than the timeframe set in the Constitution. This has also been found by respected civil society organizations such as the Albanian Helsinki Committee.

Nevertheless, the European Commission, US government, and its representatives in Albania, as well as the Albanian government, have been at pains to describe the progress of the justice reform process as by and large following the “expected timelines.” It is worth looking some of these claims, and compare them with the current reality.

In October 2017, EU spokesperson Maja Kocijančič claimed to Exit:

As the European Commission leads the International Monitoring Operation, we are aware that complex inception and preparatory steps have advanced in line with the expected timelines for the vetting institutions to carry out their tasks.

And as recently as April 2018, the European Commission’s Progress Report stated:

Implementation of the various components of the reform is progressing well, in line with the legal provisions, in terms of steps and calendar. (p. 3)

Let me be clear: these statements are untrue. For example, according to the Constitution the KLP and KLGj should have been installed in April 2017. Therefore, progress is not “in line with the legal provisions.”

Such devious claims about timelines are often measured according to the “key moments” of installing the new judicial bodies and SPAK and BKH, which depend on the formation of the KLP.

In September 2017, EU Ambassador Romana Vlahutin stated during the opening of the Second EU Summer School:

Justice reform, the most demanding and complex reform of all, is now finally to be implemented, with vetting starting in less than two weeks. Formation of new institutions including special prosecution for corruption and organized crime [SPAK] hopefully by the end of this year.

This didn’t happen.

Trying again in April 2018, US Ambassador Donald Lu expressed his belief that “the Special Prosecution Office (SPAK) and the National Bureau of Investigation (BKH) will be installed this summer.” And during a debate in The Hague in May 2018, Minister of Interior Fatmir Xhafaj tried to lower the stakes by claiming that the KLP, KLGj, and KED will be installed before the summer. None of this has actually happened.

Meanwhile, internal documents of the EU Delegation in Tirana dated to March 2018 showed that they themselves no longer believed their own Progress Report. Still it was published and celebrated by the Rama government.

So what then are precisely the EU’s “expected timelines”? What do they depend on? Are these the deadlines enshrined in the 2016 Constitution? If so, we are already since February 2017 in an unacceptable legal and constitutional vacuum and everything is utterly too late. If the EU’s timelines do not follow the deadlines in the Constitution, apparently there is some other institution “above” the Albanian Constitution that is setting “realistic” deadlines. But from the completely inconsistent claims of the EU Delegation itself no real timeline can be inferred.

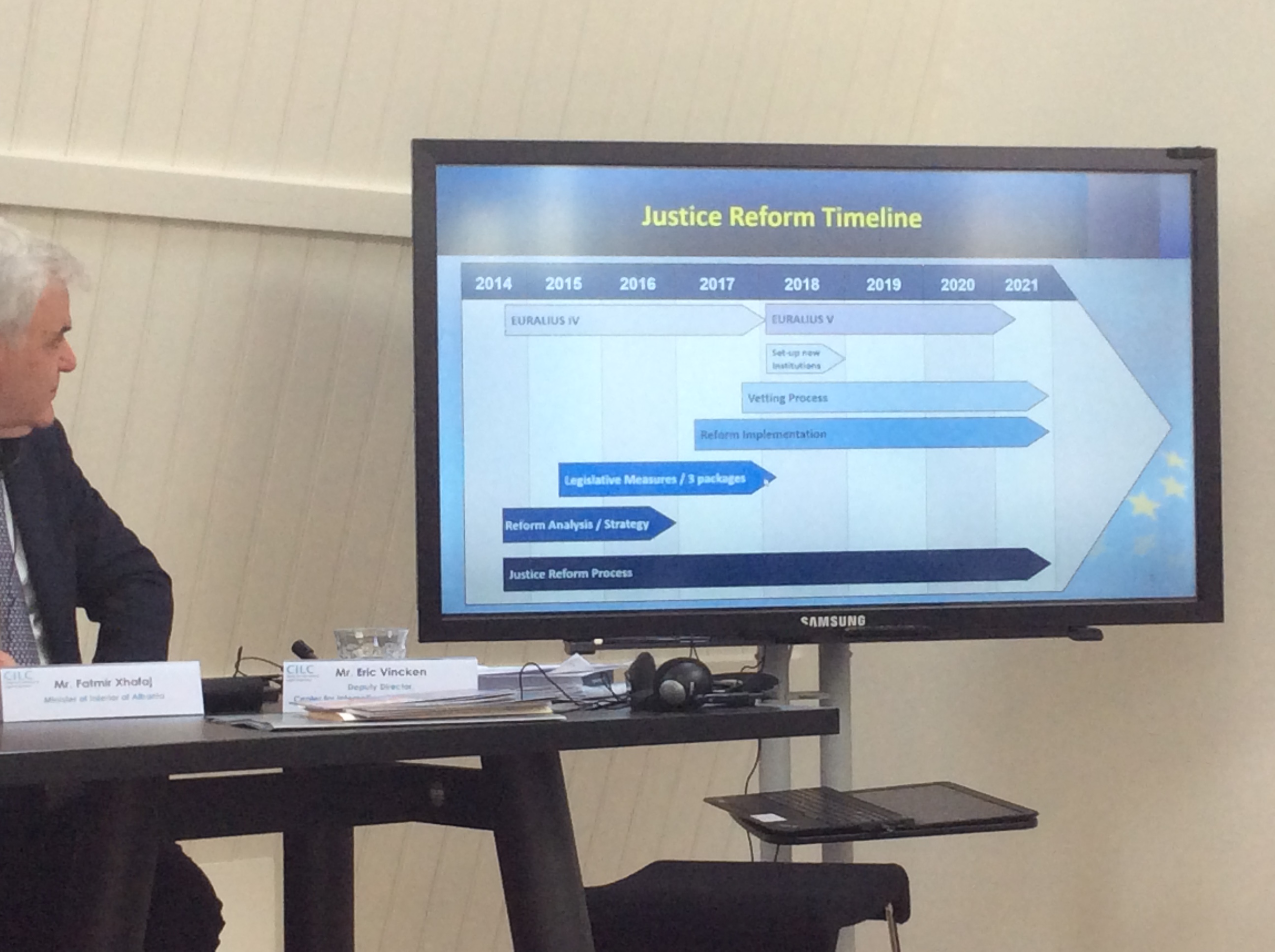

The closest to a timeline I have seen is a slide from EURALIUS, in which the vetting is expected to last until the next parliamentary elections in 2021, lasting even beyond the mandate of the EURALIUS V mission. But this unspecified and general timeline may itself be the result of wishful thinking, as so far not a single foreign diplomat has been able to offer a timeline that is based on the procedural steps laid out in the Constitution and other justice reform laws, as well as the actual progress of the vetting.

In order to so, one first needs to separate the different but interrelated processes that influence such a timeline:

- Progress of vetting by the Independent Qualification Commission (KPK)

- Progress of appeals at the Special Appeals Chamber (KPA)

- Progress of appeals at Constitutional Court/European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR)

- Procedures for the installation of the new judicial bodies

The vetting progress made by the KPK is perhaps the most transparent and most easily calculable. At the moment, 41 magistrates have passed the vetting, and the KPK is operating with an average of 6–7 cases per week. If this pace is continued, we are looking at 110–130 more weeks until all magistrates have passed the first round of vetting. This brings us to late 2020.

At the moment 8 cases have been appealed at the KPA, with only 1 receiving a verdict. The time between appeal and KPA session seems to however somewhere around 6 weeks. So unless an extraordinary amount of magistrates appeals their case, the KPA appears irrelevant in any timeline compared to the progress of the KPK.

At the moment, there have been no further appeals at the Constitutional Court and the ECtHR. However, this may change in the near future. Prosecutor Rovena Gashi has already implied that she did not receive a fair trial, and she will most likely appeal to the KPA. An appeal to the Constitutional Court after that is technically possible under the new Constitution (as pointed out by the Venice Commission), but most likely Gashi will be able to argue that because the highest court has no quorum, she can bump her case up to the ECtHR (where the government has been failing to get anyone of their preference nominated). I already discussed such a scenario last year, and none of the outcomes are good.

Any vetting case before the ECtHR would no doubt have utterly disastrous effects on any “timeline.” Different from the Venice Commission, which merely reviewed the vetting legislation, the ECtHR would have to evaluate the entire body of verdicts by the KPK and KPA and establish whether indeed these ad-hoc institutions have been capable of holding a fair trial. Considering the backlog at the ECtHR, this process would take several years, during which in theory the establishment of one or more new judicial bodies would be held in limbo.

Because as long as the ECtHR has not determined whether a candidate for KLGj/KLP/KED was rightfully dismissed, it seems unlikely that new or replacement candidates can be nominated. And what if the ECtHR finds that a candidate was not rightfully dismissed? Are they then reinstated on the candidate list? All of these are terrible legal uncertainties hovering over the vetting process and are without any precedent in Albanian legal and political history. And no one is talking about them or considering their consequences.

Now, let’s assume for the moment that by some miracle such a calamity is averted. How do the election procedures for the KLP and KLGj actually influence the vetting timeline?

As I have explained before, the result of the current round of vetting of candidates for the KLP and KLGj will be that not enough candidates will have successfully passed the vetting. This is already the case for the KLGj, and most probably will also happen with the KLP.

As a result a new round of applications need to be held, which can only be opened once Parliament reopens in September. Once this new round is held, any list of successful applicants will need to pass Parliament, which, according to the Constitution, should take less than a month, even though the election process itself is terribly complicated, and will need some level of cooperation by the opposition. It should be noted, however, that the last time this application process was tainted by illegal procedures by Speaker of Parliament Gramoz Ruçi, and that political relations have seriously deteriorated in the meantime. Should the PS push through an additional candidate list on its own, this would imply the complete politicization of the new governing bodies of the judiciary and a disastrous failure of the justice reform.

If, again by some miracle, political consensus is found, the dossiers of these new candidates need then to be opened and evaluated by the KPK, and so on. There is little chance of all of this happening by the end of 2018.

For the KED, the situation is even worse. If not a full KED passes the vetting this year, no Constitutional Court can be formed until a full KED passes the vetting next year, and so on, until everyone has been vetted and no non-vetted members can be elected to the KED. This means that the Constitutional Court risks being paralyzed until 2021, while the government is supposed to pass essential changes to the Electoral Code before the 2021 elections – which most certainly will be appealed at the Constitutional Court, which will not exist.

So that’s what a realistic timeline implies.