According to Constitution art. 149(4), there is among the 11 members High Prosecutorial Council (KLP) one member from civil society. The KLP is one of the most important new institutions that are the result of the judicial, and has wide-ranging power over the Prosecution Office, including proposing candidates for the position of the Prosecutor General, and appointing prosecutors throughout the judicial system. The absence of the KLP, which according to the Constitution should have been installed in April, has led in recent weeks to a number of unlawful situations, including the appointment of a Temporary Prosecutor General and her subsequent personnel changes in the Prosecution Office.

The search for the one KLP member from civil society has been one of the main reasons for the delay of the installation of the KLP, and has been a search that went through 6 public calls, only to suddenly result in the miraculous appearance four ostensibly qualifying candidates presented to Parliament in early January, after the election of the Temporary Prosecutor General.

An inspection of the report prepared by the National Ombudsman about the entire selection procedure shows that the Civil Society Commission (KShC), which conducted the search, was at times arbitrary, and at certain points failed to follow proper procedures. The way in which Parliament subsequently “ranked” these candidates is even more alarming.

The Civil Society Commission

The KShC was headed by Andi Dobrushi, director of the SOROS/Open Society Foundation in Albania, and further included Rajmonda Bozo, Ina Xhepa, Elsa Ballauri, and Atmir Mani. Its first meeting was held on February 27, 2017. Five candidates had applied for the position, Bledar Alia, Mevlut Derti, Drita Avdyli, Alban Tutulani, Plarent Ndreca, and in two meetings on March 1 and March 10 they were evaluated by the KShC.

Alia, Derti, and Avdyli were rejected because they failed to pass the formal criteria for the position, including a master degree in law, 15 years of experience as a jurist, and the support of 3 civil society organizations (following art. 152 of law no. 115/2016 “On governance institutions of the justice system”).

Ndreca and Tutulani were both asked for further clarifications, including the civil society projects in which they were involved. They were both later rejected in a meeting on April 4. Ndreca because he couldn’t prove to have worked for an NGO for at least 5 years, and Tutulani because he had been dismissed in 2002 from the Prosecution Office through a presidential decree.

Meanwhile, Bledar Alia had filed a complaint because the KShC had not accepted his work for an EU-registered NGO as valid. Indeed, art. 152(2)(d) doesn’t specify that the NGO that the candidate has worked at should be Albanian. Nevertheless, the KShC concluded that is unable to revisit any of its decisions based on complaints:

After the discussion of this complaint, the commission decided that its decisions as a collegial organ are final decisions and cannot be revisited regardless of the complaints presented by the applicants.

At the same time, the KShC decided to inform Ndreca (but not Alia) that he could file a complaint against the rejection of his application at the Administrative Appeals Court in Tirana. Ndreca filed a claim, which was rejected by the court.

In the meeting of May 9, the KShC evaluated two new candidates, Mimoza Qinami and Tartar Bazaj. Qinami failed to prove that she had not worked as a advocate for at least two years, but different from previous candidates, she was allowed to send in additional documents to fill this gap in her application until the next meeting. Also Bazaj, who appeared to lack a Master diploma recognized by the Albanian state, was not allowed extra time to get his documents in order. It thus appears that the KShC operated with different standards for different candidates.

In the meeting of May 11, Bazaj’s application was rejected based on formal criteria. Although this was the next meeting after the meeting of May 9, the KShC did not review Qinami’s application, giving her again extra time to find the right documents.

An extraordinary meeting was held on May 29, to evaluate new evidence provided by the Prosecution Office concerning Tutulani’s tenure and dismissal. Again the KShC voted not to revisit their decision. A claim of Tutulani was rejected by the Administrative Appeals Court in Tirana. Meanwhile, the commission seems to have completely forgotten about Qinami.

We are by now at the third call for candidates, and in a meeting of July 26, three new candidates have applied, Kostandin Kazanxhi, Lindita Xhillari, and Vasil Shandro. Again we find procedural curiosities. Even though Kazanxhi should be disqualified based on the formal criteria, the KShC gives him, like Qinami, extra time to come up with more documentation to support his candidacy. Both Xhillari and Shandro pass the formal criteria, and the KShC asks them for further clarifications regarding their engagement with civil society, as it had done with Ndreca and Tutulani.

In a meeting on August 2, Shandro’s candidacy is rejected. Kazanxhi’s candidacy, in spite of the fact that it violates art. 152(2)(f) (he has family or first degree relatives who are incumbent High Prosecutorial Council members or candidates), the KShC certifies that his candidacy meets the formal criteria. The candidacy of Xhillari is also judged to meet the formal requirements.

Even though the report fails to declare when Qinami sent in her missing documentation, and when the KShC took its decision to formally qualify her candidacy, she appears, with Kazanxhi and Xhillari, on the list of candidates that will be interviewed by the commission.

The interviews are held on August 31, and all three candidates are scored and ranked. But during an extraordinary session on September 7, it appears that the International Monitoring Operation (ONM) evaluated the candidacies of Kazanxhi and Xhillari negatively, after which they are rejected based on art. 152(2)(ç), which determines that candidates should have “a prominent social profile, high moral integrity and high professional qualification in law and human rights.”

Both Kazanxhi and Xhillari file claims at the Administrative Appeals Court in Tirana. They are both rejected. This again leaves Qinami as the only qualified candidate.

More than 2 months later, another candidate shows up, Vladimir Vladaj. He is disqualified.

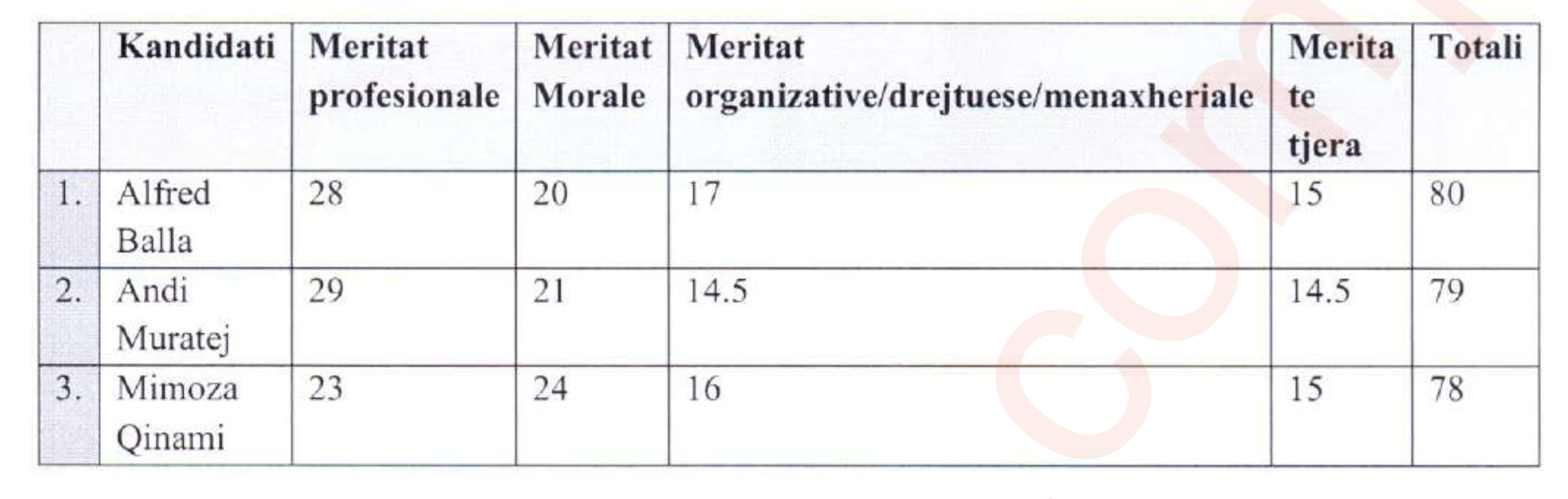

And then suddenly, in the midst of the political conflict about the Prosecutor General on December 18, five new candidates show up after the sixth open call, Alfred Balla, Andi Muratej, Bledar Bejri, Entela Baci (Hoxhaj), and (again) Vladimir Vladaj. Balla, Muratej, and Baci are deemed qualified, while Bejri and Vladaj are rejected. The first three are interviewed, scored, and ranked on December 20. Together with Qinami, they are forwarded as candidates to the Secretary General of Parliament, Genci Gjonçaj, without awaiting the report of the ONM.

The Secretary General of Parliament

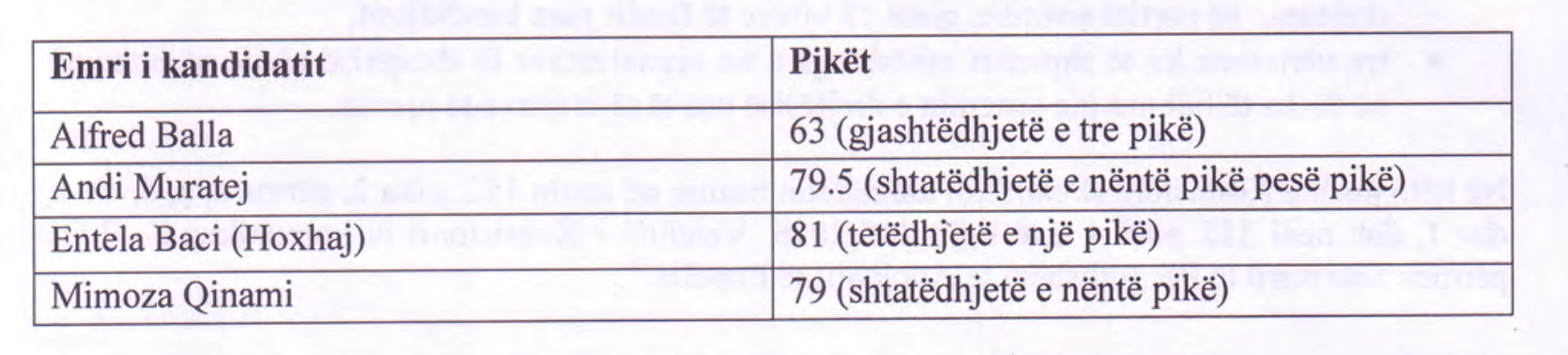

Gjonçaj does a final review of the candidates, and on January 15 sends his own final scores to Parliament:

So the highest scoring candidate according to the KShC, Entela Baci, has been removed completely, while the lowest scoring candidate, Alfred Balla, has now come out on top.

The ONM evaluation reports for Alfred Balla and Andi Muratej, which have come out in the meantime, are even more troubling. According to the ONM, Muratej doesn’t fulfill the formal criteria, while the platform Balla – the highest scoring candidate according to Gjonçaj – is “nearly completely plagiarized from the platform of another candidate (Plarent Ndreca).” Both the ONM and Gjonçaj also reject Baci, based again on art. 152(2)(ç).

Both Xhillari and Kazanxhi’s candidacies were rejected after their evaluation by the ONM, but apparently a similar evaluation is not enough for Gjonçaj to reject Balla and Muratej. The question is obviously whey the KShC was unable to wait for the ONM evaluations to be received, and only then send a final candidate list to Parliament. Why was there a sudden hurry? Was it international pressure? Or the fear that with again Qinami as the last woman standing, the process would many more months?

So, to sum up, according to the ONM the only candidate that passes all formal and moral requirements is Mimoza Qinami, even though she has received the lowest points from the Secretary General of Parliament Genci Gjonçaj, and her approval by the KShC remains partially undocumented, while the highest ranked candidate, Alfred Balla, has copied most of his application from someone else.

May the best candidate win!

Summary of candidates

- Bledar Alia (rejected based on formal criteria, March 1)

- Mevlut Derti (rejected based on formal criteria, March 1)

- Drita Avdyli (rejected based on formal criteria, March 1)

- Alban Tutulani (rejected based on formal criteria, April 4)

- Plarent Ndreca (rejected based on formal criteria, April 4)

- Mimoza Qinami (approved, date not reported; approved by ONM)

- Tartar Bazaj (rejected based on formal criteria, May 11)

- Kostandin Kazanxhi (approved in violation of art. 152(2)(f) of law no. 115/2016, August 2; rejected after ONM evaluation, September 7)

- Lindita Xhillari (approved, August 2; rejected after ONM evaluation, September 7)

- Vasil Shandro (rejected based on formal criteria, August 2)

- Vladimir Vladaj (rejected based on formal criteria, November 23; rejected based on formal criteria, December 18)

- Alfred Balla (approved, December 18; rejected by ONM)

- Andi Muratej (approved, December 18; rejected by ONM)

- Bledar Bejri (rejected based on formal criteria, December 18)

- Entela Baci (Hoxhaj) (approved, December 18; rejected by Secretary General of Parliament, January 15)