On Tuesday, the European Commission published its Progress Report on Albania. Yesterday I already provided a first read-through of its 100+ pages, pointing out that the document at times reads more like Albanian government propaganda than a factual basis on which proper decision making by the European Parliament and the European Council can be made.

Today I would like to take a look at the broader question of EU enlargement and the EU accession process in which the Western Balkan countries, including Albania, are currently involved.

The EU faces an impossible dilemma, which became eminently clear during an exchange between French President Emmanuel Macron and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker. In an address to the European Parliament, President Macron declared:

I will only support an enlargement when there is first a deepening and a reform of our Europe. […] I don’t want a Balkans that turns toward Turkey or Russia, but I don’t want a Europe that, functioning with difficulty at 28 and tomorrow as 27, would decide that we can continue to gallop off, to be tomorrow 30 or 32, with the same rules.

In a response, President Juncker said:

If we remove from these countries, in this extremely complicated region, I should say tragically, a European perspective, we are going to live what we already went through in the 1990s. […] I don’t want a return to war in the Western Balkans.

Macron’s idea is for the EU to enter into a process of reform, into a “new project” for the EU before committing to further enlargement. The argument would be that only through reform the EU would be able to counter the rise of nationalist authoritarianism in EU states such as Hungary and Poland, and the rise of the extreme right in Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and France, which feed on anti-EU sentiments. The cost of entering this reform process, however, would be to hold off enlargement till further notice, shattering the hopes of the Western Balkan countries of accession within the next decade, and thus enabling the rise of nationalism and worse at the borders of the EU, as Juncker warns of.

The trade-off that Macron proposes is therefore between the growth of nationalism within EU states in response to the perceived lack of democracy of the EU versus the growth of nationalism in the Western Balkans in response to the freeze on enlargement.

The dilemma, however, lies not only in the decision regarding the reform of the EU and the freeze on enlargement. It lies in the very process of enlargement itself.

Currently, EU enlargement is controlled by the executive branch of the EU government, the European Commission (EC), with direct little input from either the European Parliament or the European Council. The EU accession process is therefore largely perceived and measured as a harmonization process between Albanian legislation and the EU acquis communautaire, negotiated between the government and unelected officials from the EC, presented by the EU Ambassador in Albania.

The emphasis on executive-branch-driven legislative initiative, rather than creating broad civil support and understanding of the EU integration process, both inside and outside the EU, thus inadvertently leads to precisely the type of politics that Macron warns for: authoritarian, executive-driven modes of governance. In other words, the structure of the enlargement process ironically replicates precisely those modes of governance that oppose the underlying values of the EU.

Seen in that light, Macron’s call to reform makes a lot of sense. However, a truly democratic and broadly, EU-wide supported reform of the EU would necessarily touch upon the core of the enlargement process, making accession potentially much more comprehensive and difficult: rather than ticking of legislative boxes, it would entail a thorough reform of civil and political mentality. So even without a freeze on enlargement itself, the reform of the EU as proposed by Macron – no matter how general and vague – threatens the core of the current enlargement regime.

No wonder that Juncker responds with the hyperbole of the return of war. EU reform would not only threaten the enormous power he and his commissioners have over candidate member states; in its ideal form it would open up his bureaucratic machine to active scrutiny by democratically elected EU bodies such as the European Parliament. His threat of a”return to war” is not only a rhetorical gesture through which he aims to protect the “inevitable” progress of the enlargement process; the enlargement process itself is one of the most important symbols of the large, relatively unchecked power held by the European Commission and the Directorates-General.

EU enlargement is founded on a strong and powerful executive branch, both inside the EU and in the candidate state. Any real reform would threaten that lopsided power balance.

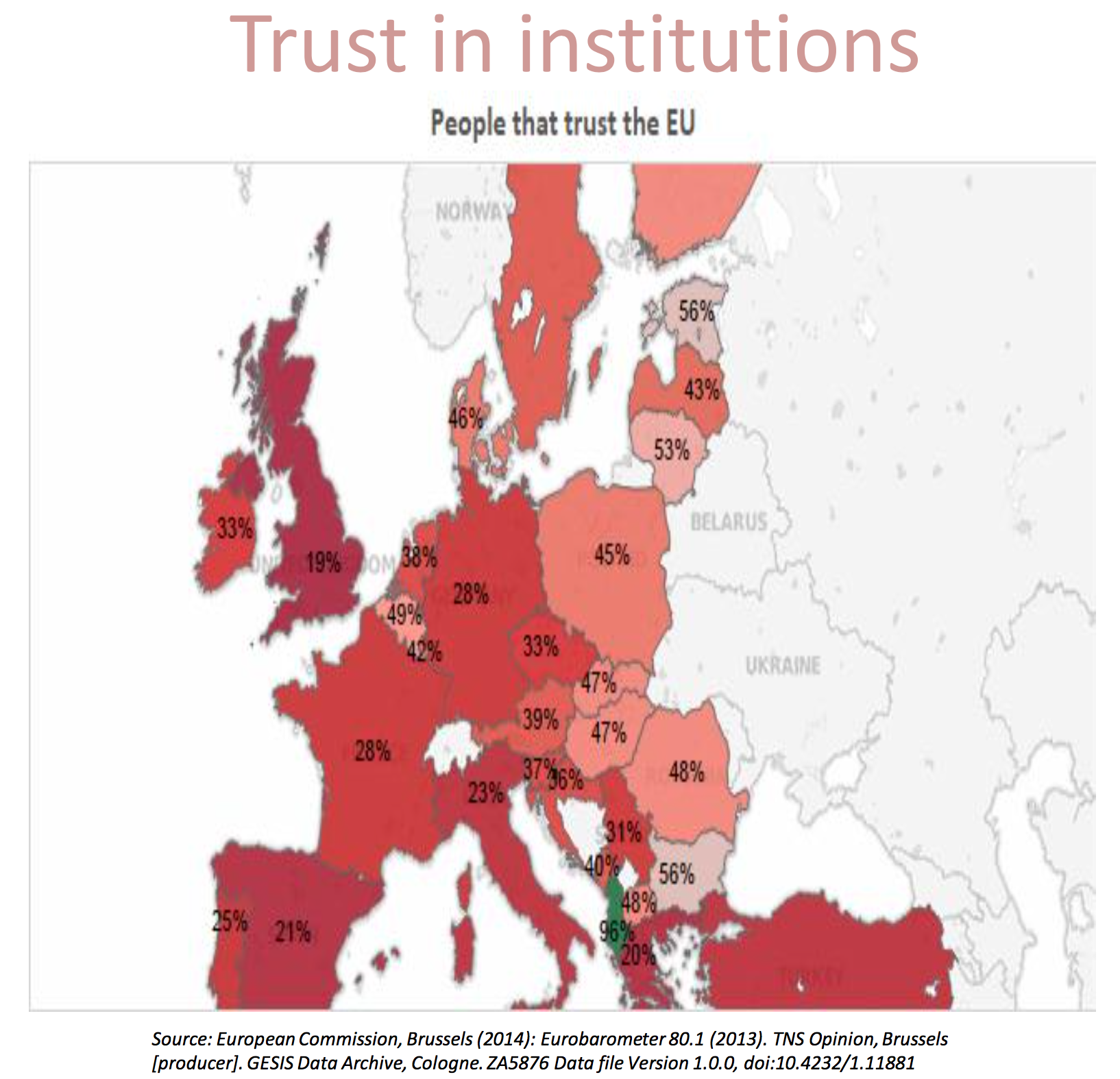

At the same time, Juncker is very right in pointing out that explicitly freezing the accession process in Western Balkan countries would have dramatic consequences, especially in Albania. 96% of Albanians trust in the EU, by far the highest number anywhere in Europe.

Albanian national politics, ever since 1991, has been built on the promise of European integration. It is basically the only point on which all political parties agree and it is perceived as an absolute fact that will trump any other political considerations. As a result, the Albanian political discourse is of a poverty that is rarely seen. Every issue pertaining to governance basically boils down to the question “Will it bring us closer to Europe?” or worse, “Will the EU Ambassador back it up?” Political debate is held purely along this axis, with questions of sovereignty, public good, sound economic policy, and other “non-key priorities” relegated swiftly to the back seat. The EU is one of the two crucial political factors in Albania.

If the EU accession horizon were to fall away, only the other remains: organized crime. In absence of an EU Ambassador to prop up the government and give it a veneer of purpose and direction, it would lose all of its legitimacy, as it will prove unable to provide any concrete improvements for the population; most services have already been privatized by the current Rama government and only few means of soft state power remain. Faced with complete disillusionment, the Albanian population would reject the entire political system, which will hence return to a full-fledged patronage system financed by criminal activity and drug trafficking.

This, and not war, would be a more realistic future scenario should the EU explicitly suspend enlargement. At the same time, any post-reform EU would most certainly change its enlargement aims and procedures, thus making it even more difficult for Albania to accede to the EU.

Reforming the EU carries an existential threat for the EU and serious risks of destabilizing its periphery in the short term, potentially even indefinitely foreclosing enlargement. However, not reforming it will continue to nourish the bad seeds of nationalism and authoritarianism both inside the EU and in the candidate member states. There are no good options, but the EU will have to choose one.