Many believe introducing a qualified majority would require an arduous treaty change, but this is not true. If a qualified majority is not introduced in the EU enlargement decision-making, the whole process will die, write Srdjan Cvijic and Zoran Nechev.

Dr Srdjan Cvijic and Zoran Nechev are Europe’s Futures Fellows of the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna.

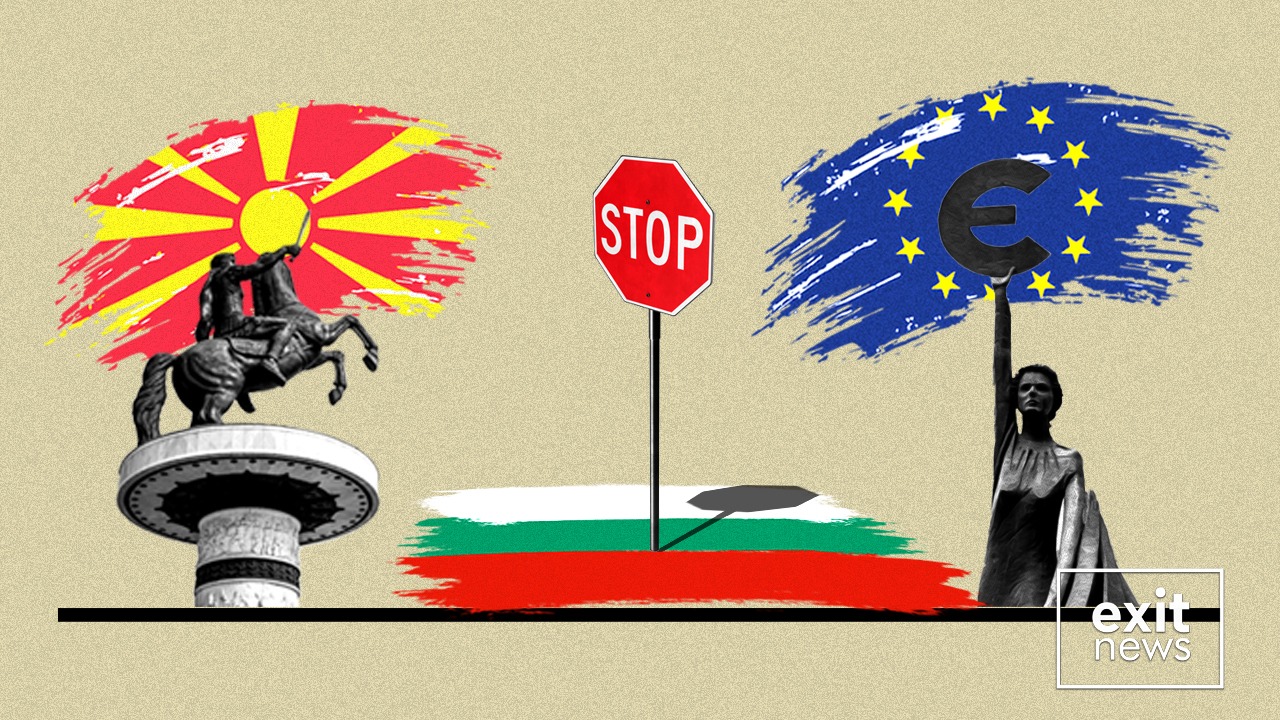

On 23 June, many hope for Bulgaria to lift its veto that would allow the European Council to open first negotiating clusters with North Macedonia and consequently, with Albania, whose further progress in the EU accession was conditioned by that of its eastern neighbour.

An unlikely greenlight of the Council for North Macedonia would have been possible thanks to an agreement discreetly negotiated between the governments in Sofia and Skopje in the weeks preceding the Council meeting.

Chaperoned by the French, this agreement was intended to send a positive signal to the Western Balkans EU membership hopefuls that the enlargement process is not dead and buried, at least for this part of Europe. Yet the truth is very different. Even if it passes, the deal would create a dangerous precedent, making a successful future enlargement of the EU, be it for North Macedonia or Ukraine, highly unlikely.

The Bulgarian veto has nothing to do with economic and democratic principles governing the EU enlargement process. They are about the nationalistic bullying of Skopje by Sofia. Similar policies normally have no place in relations between EU member states.

Bulgarian blocking of North Macedonia’s progress towards EU membership would be as if, in 2004, Germany had conditioned Polish accession into the EU by demanding that Warsaw relativises the role of German occupying forces during the Second World War. Or as if Denmark would have required Stockholm in 1995 to call the Swedish language Danish.

Not just that they block Skopje’s accession process, but these Bulgarian identarian policies would have been translated into the EU negotiating framework with North Macedonia.

And not just that, Bulgarian demands have been effectively elevated to the level of the fundamentals, bringing bilateral issues and rule of law to a same level, thus allowing the EU via Bulgaria to stop North Macedonian accession process any time, on any other negotiating cluster, not because the rule of law and democracy, but because of language and history.

Such a proposal will likely kill North Macedonia’s accession progress as the local political elites will prove unable to implement it.

The ability of member states to veto common EU foreign policy decisions because of the unanimity rule goes beyond the EU enlargement process. In 2020, Cyprus blocked a decision to impose new sanctions against Belarus over an unrelated dispute with Turkey.

In 2017, Greece blocked the EU statement criticising China’s human rights record. Orban’s Hungary has a particularly recidivist behaviour when it comes to thwarting an EU consensus in foreign policy. Hungary has repeatedly blocked or tried to block common EU statements at the United Nations and other multilateral fora: on criticising China’s human rights record and on the Middle East Peace Process.

Consensual voting on foreign policy matters will make it difficult for the EU to defend itself against direct or indirect future threats coming from Moscow as the conflict in Ukraine lingers on.

To make it possible for the EU to play the role on the global stage, in September 2018, the Commission proposed extending qualified majority voting — 55 per cent of member states representing at least 65 per cent of the EU population — to three specific foreign policy areas: a collective response to attacks on human rights; an effective application of sanctions and civilian security and defence missions.

In June 2021, the former German foreign minister Heiko Maas called for the abolishment of unanimity in the EU foreign policymaking. Maas said that the EU should not allow itself to be “held hostage by the people who hobble European foreign policy with their vetoes…If you do that, then sooner or later, you are risking the cohesion of Europe. The veto has to go, even if that means we [Germany] can be outvoted.”

The position of the present German government is no different. In the June 2018 Meseberg Declaration, France and Germany called for expanding the qualified majority to Common Foreign and Security Policy to increase the effectiveness of EU decision-making because of increasing security challenges.

Asked how to accommodate potential new member countries, including Ukraine and Moldova, the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen recently stated that “in foreign affairs, we really have to move to qualified majority voting”.

Aware that some EU member states would be unready to entirely renounce the right of veto from the EU accession process, together with a group of experts and former officials from all over Europe, the two of us proposed to abolish it from the intermediary stages of the EU enlargement negotiations only. For the opening and closing of the negotiating clusters, unanimity would still be required.

Many believe introducing a qualified majority would require an arduous treaty change. This is not true. For the alteration of a legislative procedure, in this case, it would be enough for the next Council meeting to unanimously decide to abolish unanimity in above mentioned foreign policy areas.

In 2017, when Ukraine passed a new law on education, several minority groups reacted with criticism. Yet, while Bulgaria, Romania and Moldova, who all have sizeable minorities in the country, worked constructively with the Ukrainian side and the Venice Commission to reform the law, the Hungarian government alone threatened to “block and boycott all initiatives made by Ukraine, and all initiatives which are important for Ukraine” at the EU level unless the law is dropped.

The Hungarian reaction to Ukraine’s education law is just one example of the Orban government’s general cosying up to Putin. Whereas the Russian aggression on Ukraine made a more severe rebellion from Budapest difficult, it is not excluded that Hungary, like Bulgaria is doing to North Macedonia, may decide to block Ukraine in the future.

If a qualified majority is not introduced in the enlargement process soon, the granting of the candidacy status to Ukraine would quickly become meaningless, and Kyiv’s European perspective, like that of North Macedonia or any other candidate and potential candidate country, nothing but a pipe dream.